Inside Québec – December 2008

by Maurie Alioff

Neverland

Once upon a time, Winnipeg`s genius kitschmeister Guy Maddin offered the world Careful, his homage to operatic melodrama, early filmmaking technique, and the defunct German genre known as the Mountain Film. Careful`s 19th century characters dwell in a Swiss village so precariously positioned, it might at any moment tumble into the void below. The anxious villagers try to avoid an apocalyptic avalanche by surgically muting their animals and gagging “vociferous children.”Surprisingly, inexplicably, Quebec actor Luc Picard`s second outing as a director recalls the dreamy archaism and overheated melodrama of Maddin`s 1992 film, as well as Terry Gilliam movies, visions from former Yugoslavian Emir Kusturica, and tales like The Old Woman Who Lived in a Shoe. As an actor, Picard usually works in a grim realist mode far removed from Babine’s source material: story-teller Fred Pellerin’s live one-man-show, Il faut prendre le taureau par les contes (You Have to Grab the Bull by the Stories).An ardent Quebec nationalist, Picard played an FLQ kidnapper in Pierre Falardeau`s Octobre (1994) and the martyred 19th century patriot hero François-Marie-Thomas de Lorimier in the same director’s 15 février 1839 (2001). He won a Genie for his scary incarnation of a murderous cult leader in Savage Messiah (2002) and was a terminal alcoholic in Bernard Émond’s 20h17 Rue Darling. For L’audition, Picard’s writing and directorial debut, he cast himself as an unhappy thug who prefers acting to beating the crap out of losers who annoy his boss.On the other hand, Babine is all fairy-dust, fireflies, and flower petals as it recounts the events that transpire in Pellerin’s mythic St. Élie de Caxton, a village nestled in timeless mountains that suggest a toy world enclosed by a glass ball. Opening like many fairy tales on a magical birth, a woman the villagers think of as a witch (Isabel Richer) brings the film’s eponymous hero to life. La Sorcière`s Babine (Vincent-Guillaume Otis) grows up into a shuffling, harmonica-playing Fool, a must for every village, the voiceover narrator (Pellerin himself) tells us.The movie`s plot kicks in when Babine’s friend, a kindly old priest (Julien Poulin), dies in a fire, and the good burghers blame the Fool for the catastrophe, just as they believe he`s guilty of every other lousy thing that happens, including the

Shoe. As an actor, Picard usually works in a grim realist mode far removed from Babine’s source material: story-teller Fred Pellerin’s live one-man-show, Il faut prendre le taureau par les contes (You Have to Grab the Bull by the Stories).An ardent Quebec nationalist, Picard played an FLQ kidnapper in Pierre Falardeau`s Octobre (1994) and the martyred 19th century patriot hero François-Marie-Thomas de Lorimier in the same director’s 15 février 1839 (2001). He won a Genie for his scary incarnation of a murderous cult leader in Savage Messiah (2002) and was a terminal alcoholic in Bernard Émond’s 20h17 Rue Darling. For L’audition, Picard’s writing and directorial debut, he cast himself as an unhappy thug who prefers acting to beating the crap out of losers who annoy his boss.On the other hand, Babine is all fairy-dust, fireflies, and flower petals as it recounts the events that transpire in Pellerin’s mythic St. Élie de Caxton, a village nestled in timeless mountains that suggest a toy world enclosed by a glass ball. Opening like many fairy tales on a magical birth, a woman the villagers think of as a witch (Isabel Richer) brings the film’s eponymous hero to life. La Sorcière`s Babine (Vincent-Guillaume Otis) grows up into a shuffling, harmonica-playing Fool, a must for every village, the voiceover narrator (Pellerin himself) tells us.The movie`s plot kicks in when Babine’s friend, a kindly old priest (Julien Poulin), dies in a fire, and the good burghers blame the Fool for the catastrophe, just as they believe he`s guilty of every other lousy thing that happens, including the appearance of a giant flying bull. When the new curé (Alexis Martin) arrives in the village, the vicious fanatic makes more than one attempt to hang the melancholy, haplessly romantic Babine. Another eccentric, Toussaint Brodeur (Picard), tries his best to protect the boy, who is, of course, an emblem of innocence in stark contrast with the kind of theological totalitarianism that poisoned Quebec`s real past. Distributor Alliance-Vivafilm`s decision to release Babine on the cusp of the holiday season positions it as a family picture. Even the film’s dark edge and sexual shenanigans are mild compared to Careful’s rooting around in mother-son incest and other deviations. As I write, the Quebec film industry`s hope that Babine will rake in a pot of gold is being nurtured by the film`s first ten days of box-office. Playing on 76 screens, Picard’s fable earned over $1 million, and ranked 2nd in the province, just after Twilight. Whether or not this unconventional picture will score as big as Quebec’s hit comedies remains to be seen. Whatever the numbers, Babine, which Picard dedicated “to our fathers,” is a guaranteed award-winner that will trigger plenty of learned analysis. As for other recent releases, Simon Lavoie’s Le déserteur (see November’s Inside Quebec), a modest picture about an AWOL World War II soldier, did better box office than Paul Gross’ Passiondaele, a $20 million aspiring epic about a World War I soldier who dies in battle. And Catherine Hardwicke’s Twilight, while the top earner on its opening weekend, made 10% less in Quebec than in the rest of North America. This result despite the film`s casting of Montrealer Rachelle Lefevre as Victoria, one of the bad vampires who disrupts the delirious romance between Bella Swan (Kristen Stewart) and the angelic bloodsucker (Robert Pattinson), who would never go near her neck.

appearance of a giant flying bull. When the new curé (Alexis Martin) arrives in the village, the vicious fanatic makes more than one attempt to hang the melancholy, haplessly romantic Babine. Another eccentric, Toussaint Brodeur (Picard), tries his best to protect the boy, who is, of course, an emblem of innocence in stark contrast with the kind of theological totalitarianism that poisoned Quebec`s real past. Distributor Alliance-Vivafilm`s decision to release Babine on the cusp of the holiday season positions it as a family picture. Even the film’s dark edge and sexual shenanigans are mild compared to Careful’s rooting around in mother-son incest and other deviations. As I write, the Quebec film industry`s hope that Babine will rake in a pot of gold is being nurtured by the film`s first ten days of box-office. Playing on 76 screens, Picard’s fable earned over $1 million, and ranked 2nd in the province, just after Twilight. Whether or not this unconventional picture will score as big as Quebec’s hit comedies remains to be seen. Whatever the numbers, Babine, which Picard dedicated “to our fathers,” is a guaranteed award-winner that will trigger plenty of learned analysis. As for other recent releases, Simon Lavoie’s Le déserteur (see November’s Inside Quebec), a modest picture about an AWOL World War II soldier, did better box office than Paul Gross’ Passiondaele, a $20 million aspiring epic about a World War I soldier who dies in battle. And Catherine Hardwicke’s Twilight, while the top earner on its opening weekend, made 10% less in Quebec than in the rest of North America. This result despite the film`s casting of Montrealer Rachelle Lefevre as Victoria, one of the bad vampires who disrupts the delirious romance between Bella Swan (Kristen Stewart) and the angelic bloodsucker (Robert Pattinson), who would never go near her neck.

The Hell Next Door

You don’t have to be a palpitating tween chick to be seduced by the Vampire Lite Twilight, which is not true horror, a genre label Montreal producer Pierre Even rejects for his new movie, 5150 rue des Ormes. Currently in production, the film depicts the ordeal of a young man who falls into the clutches of demented neighbours. Rue des Ormes is novelist-screenwriter Patrick Sénécal`s second collaboration with Éric Tessier, whose 2003 adaptation of Sénécal’s chiller Sur le seuil also rooted around in a world of psychopathic violence. Tessier’s latest features rising star Marc-André Grondin as the victim of Sénécal’s demonic family. Grondin’s irresistible performance in Jean-Marc Vallé’s 2005 hit C.R.A.Z.Y. launched the actor into a career that has included roles in Montreal filmmaker Karim Hussain’s take on Marie-Claire Blais’ novel, La Belle bête, and Steven Soderbergh’s epic bio of Che Guevara. When Grondin auditioned for C.R.A.Z.Y., also produced by Pierre Even, Vallé flipped. “I saw this fucking look,” the writer-director told me a couple of years ago. “The guy was so sexy, and he was so wild.” During the shoot, Vallé confirmed his instinct that Grondin’s charisma was matched by his talent. “He was able to do nothing, and he played violence. He played an orgasm, he was scary, he was pissed. He had to do almost everything on this film.”As for Jean-Marc Vallé’s career, he plans to shoot a dramedy about male rivalry, disco, and women’s footwear. Further down the road, he hopes to direct his own script about the Café de Flore, the legendary Saint-Germain-des-Prés bistro where Jean Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir discussed the pressures of living without meaning, Juliette Greco established black as the

collaboration with Éric Tessier, whose 2003 adaptation of Sénécal’s chiller Sur le seuil also rooted around in a world of psychopathic violence. Tessier’s latest features rising star Marc-André Grondin as the victim of Sénécal’s demonic family. Grondin’s irresistible performance in Jean-Marc Vallé’s 2005 hit C.R.A.Z.Y. launched the actor into a career that has included roles in Montreal filmmaker Karim Hussain’s take on Marie-Claire Blais’ novel, La Belle bête, and Steven Soderbergh’s epic bio of Che Guevara. When Grondin auditioned for C.R.A.Z.Y., also produced by Pierre Even, Vallé flipped. “I saw this fucking look,” the writer-director told me a couple of years ago. “The guy was so sexy, and he was so wild.” During the shoot, Vallé confirmed his instinct that Grondin’s charisma was matched by his talent. “He was able to do nothing, and he played violence. He played an orgasm, he was scary, he was pissed. He had to do almost everything on this film.”As for Jean-Marc Vallé’s career, he plans to shoot a dramedy about male rivalry, disco, and women’s footwear. Further down the road, he hopes to direct his own script about the Café de Flore, the legendary Saint-Germain-des-Prés bistro where Jean Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir discussed the pressures of living without meaning, Juliette Greco established black as the  colour of choice for boho artistes, and Johnny Depp contemplated Paris in the eyes of Vanessa Paradis. Meanwhile, Vallé’s look at Queen Victoria`s youth, a movie crediting Sarah Ferguson and Martin Scorsese as producers, is being prepped for its imminent release.Another coming attraction, Léa Pool`s Une belle mort (A Beautiful Death), began shooting in mid-November. An adaptation of a novel by veteran journalist Gil Courtemanche (Un dimanche à la piscine à Kigali), the movie removes Pool from the youthful characters she`s been exploring since 1999`s ode to teenage female turmoil, Emporte-moi (Set Me Free). In the darkly-toned new picture, the value of a sick old man`s broken life is debated during a family reunion. A while back, Pool complained to me that Telefilm Canada doubted the project even though Quebec culture agency SODEC was eager to fund it. But now both institutions are invested in what turned out to be the first official coproduction between Canada and Luxembourg, where Une belle mort has been filming.

colour of choice for boho artistes, and Johnny Depp contemplated Paris in the eyes of Vanessa Paradis. Meanwhile, Vallé’s look at Queen Victoria`s youth, a movie crediting Sarah Ferguson and Martin Scorsese as producers, is being prepped for its imminent release.Another coming attraction, Léa Pool`s Une belle mort (A Beautiful Death), began shooting in mid-November. An adaptation of a novel by veteran journalist Gil Courtemanche (Un dimanche à la piscine à Kigali), the movie removes Pool from the youthful characters she`s been exploring since 1999`s ode to teenage female turmoil, Emporte-moi (Set Me Free). In the darkly-toned new picture, the value of a sick old man`s broken life is debated during a family reunion. A while back, Pool complained to me that Telefilm Canada doubted the project even though Quebec culture agency SODEC was eager to fund it. But now both institutions are invested in what turned out to be the first official coproduction between Canada and Luxembourg, where Une belle mort has been filming.

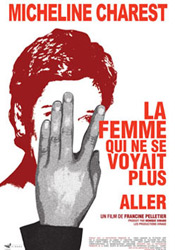

Mystery Woman

Given the troubled and ambiguous female characters she created in movies like La Femme de l’hôtel (1984) and Mouvements du désir (1994), I can imagine Léa Pool being intrigued by telejournalist Francine Pelletier’s doc, La femme qui ne se voyait plus aller (The Woman Who Lost Herself). After a run on the festival circuit, this account of TV show producer Micheline Charest’s tumble from sweet-smelling success into bottomless scandal, not to mention a preposterous death, aired recently on the CBC`s French language network. The timing of the broadcast synched up with a legal case instigated by Claude Robinson, the man widely credited with bringing on Charest’s downfall. On September 4, 1995, Robinson, a graphic designer and writer, lurched away from his TV after seeing a promo for a show called Robinson Sucroe. Created by Montreal-based, internationally known children`s programming operation, Cinar Corp, Robinson Sucroe looked like a knock-off of Robinson Curiosité, an animated show the artist had pitched to Cinar co-founders Micheline Charest and her husband Ron Weinberg. Not only did Robinson head for the nearest RCMP office and launch a multi-million dollar lawsuit that finally arrived in a Montreal courtroom last September and will be argued there until the spring, he obsessively investigated Cinar. Robinson`s relentless probing, along with other inquiries, eventually revealed that Canada`s purveyor of non-violent, moralistic kiddie TV was guilty of “total amorality,” Robinson’s lawyer says to Pelletier.Cinar`s sins included breaking tax credit rules by hiring American writers who hid behind Canadian names; siphoning money from the publicly traded company to pay for private luxuries; and sneaking $122 million (US) of company assets into personal investments. Fake companies, documents, and signatures flourished. Eventually, Charest and Weinberg agreed to paying huge financial settlements, but without admitting to any wrongdoing, or even facing criminal charges, let alone doing time. No current government agency types would speak to Pelletier for her film, but ex-Telefilm Canada head Peter Pearson says about the couple’s tax credit offences, “To construct them as monsters in this environment, I think is a misconstruction. And it didn’t matter what they were doing. They were doing what everybody else was doing.”Francine Pelletier’s The Woman Who Lost Herself suggests that Charest’s heavyweight political connections may have protected her and Weinberg from a fate like Conrad Black’s. The doc also questions why a woman

Corp, Robinson Sucroe looked like a knock-off of Robinson Curiosité, an animated show the artist had pitched to Cinar co-founders Micheline Charest and her husband Ron Weinberg. Not only did Robinson head for the nearest RCMP office and launch a multi-million dollar lawsuit that finally arrived in a Montreal courtroom last September and will be argued there until the spring, he obsessively investigated Cinar. Robinson`s relentless probing, along with other inquiries, eventually revealed that Canada`s purveyor of non-violent, moralistic kiddie TV was guilty of “total amorality,” Robinson’s lawyer says to Pelletier.Cinar`s sins included breaking tax credit rules by hiring American writers who hid behind Canadian names; siphoning money from the publicly traded company to pay for private luxuries; and sneaking $122 million (US) of company assets into personal investments. Fake companies, documents, and signatures flourished. Eventually, Charest and Weinberg agreed to paying huge financial settlements, but without admitting to any wrongdoing, or even facing criminal charges, let alone doing time. No current government agency types would speak to Pelletier for her film, but ex-Telefilm Canada head Peter Pearson says about the couple’s tax credit offences, “To construct them as monsters in this environment, I think is a misconstruction. And it didn’t matter what they were doing. They were doing what everybody else was doing.”Francine Pelletier’s The Woman Who Lost Herself suggests that Charest’s heavyweight political connections may have protected her and Weinberg from a fate like Conrad Black’s. The doc also questions why a woman  who turned a mom and pop distribution operation into a world-class production company would jeopardize the domain she so carefully constructed.The tightly-structured film packs in copious information about the product of an affluent and pampered background in Quebec city. You can recognize the woman`s sharply-angled, intensely focused face in childhood photos. An aunt says that Charest had everything, but always wanted more faster. She would cut her hair short to enhance her performance in the New York City marathon.In the summer of 2003, I almost had a close encounter with Charest. I taped an on-camera interview about Cinar for Peter Rowe`s Popcorn and Maple Syrup, a doc about Canadian film, and left the studio just before she came in for hers. It was to be her last interview. Charest, who according to a relative had “a lot of masculine energy, but not a lot of heart,” opted for multiple procedures during an April 14 2004 cosmetic surgery her friends thought she didn’t really need. She may have died that day because she was in a rush to accomplish too much too soon.

who turned a mom and pop distribution operation into a world-class production company would jeopardize the domain she so carefully constructed.The tightly-structured film packs in copious information about the product of an affluent and pampered background in Quebec city. You can recognize the woman`s sharply-angled, intensely focused face in childhood photos. An aunt says that Charest had everything, but always wanted more faster. She would cut her hair short to enhance her performance in the New York City marathon.In the summer of 2003, I almost had a close encounter with Charest. I taped an on-camera interview about Cinar for Peter Rowe`s Popcorn and Maple Syrup, a doc about Canadian film, and left the studio just before she came in for hers. It was to be her last interview. Charest, who according to a relative had “a lot of masculine energy, but not a lot of heart,” opted for multiple procedures during an April 14 2004 cosmetic surgery her friends thought she didn’t really need. She may have died that day because she was in a rush to accomplish too much too soon.

![]() Maurie Alioff is a film journalist, critic, screenwriter and media columnist. He has written for radio and television and teaches screenwriting at Montreal`s Vanier College. A former editor for Cinema Canada and Take One, as well as other magazines, his articles have appeared in various publications including The Montreal Mirror and The New York Times.

Maurie Alioff is a film journalist, critic, screenwriter and media columnist. He has written for radio and television and teaches screenwriting at Montreal`s Vanier College. A former editor for Cinema Canada and Take One, as well as other magazines, his articles have appeared in various publications including The Montreal Mirror and The New York Times.