Inside Québec – March 2009

by Maurie Alioff

Killer

Denis Villeneuve’s Polytechnique depicts the winter day in 1989 when 25-year-old Marc Lépine stuffed a semi-automatic rifle into a garbage bag and hauled it through the doors of the University of Montreal’s engineering school. Before blowing his own brains out, Lépine murdered fourteen young women and wounded thirteen other students, four of them men.

The film begins by crosscutting between two of the girls in their apartment getting ready for their day at the École Polytechnique, and the killer prepping for his. Although Valérie (Karine Vanasse), Stéphanie (Evelyne Brochu), and theunidentified murderer (Maxim Gaudette, pictured below) are fictionalizations of real people, the voiceover rant we hear is from Lépine’s actual suicide note. “I have decided to send Ad Patres (to the Fathers) the feminists who have ruined my life,” he declaims.

In the movie’s most horrific moment, which we see twice from different perspectives, the madman strolls into a classroom, forces the men to leave, and commands the girls to line up against a wall. He accuses these studious kids, ambitiously competing in a traditionally male discipline, of being feminists. When one of them says they are not, he sprays them with bullets.

After opening in early February as Quebec’s number one film at the box office, Polytechnique lost its position to Marcus Nispel’s reboot of the original Friday the 13th. There’s an irony in this linkage. Murderers like Lépine and Virginia Tech shooter Seung Hui Cho are the monstrous real-life equivalents of movie monsters like Jason Voorhees (Friday the 13th), who stalk and destroy young people – especially female young people. But like Elephant (2003), Gus Van Sant’s meditation on the Columbine massacre, Villeneuve’s black and white, 76-minute film scrupulously avoids sensationalism. It’s far removed from slasher pictures, even the great ones that invented and transcended the genre.

In Polytechnique, the killer has no cleverly sadistic funny games up the sleeve of a black trench coat. Moreover, Villeneuve never wallows in gore, or orchestrates teasing build-ups to money jolts. The film shocks with the matter-of-fact brutality of its unflamboyant, banal killer. In his grey parka, he goes about his business like a plumber, never to be melodramatically confronted by a hero. Student Jean-François (Sébastien Huberdeau) tries to come to the rescue, but fails.

A raging controversy about Villeneuve’s movie erupted before its release. The media knew that the award-winning director of 32 août sur terre (1998) and Maelström (2000), a serious guy who took an 8-year hiatus from moviemaking to “think about cinema” and be with his kids – he told me last summer – would never exploit a hugely traumatic event. Nevertheless, journalists fired off one insinuating question after another. Why would actress Karine Vanasse initiate the project and take it to producers Maxim Rémilllard and Don Carmody? Why should the relatives and friends of the victims be forced to endure the agonizing memories that would be triggered by the film’s release? Why would Villeneuve want to direct the picture, and would anyone buy a ticket to see it?

take it to producers Maxim Rémilllard and Don Carmody? Why should the relatives and friends of the victims be forced to endure the agonizing memories that would be triggered by the film’s release? Why would Villeneuve want to direct the picture, and would anyone buy a ticket to see it?

To me, invalidating a film that confronts a shared nightmare is ridiculous. If it was a mistake to make Polytechnique, then movies about the holocaust or 9/11 are also a breech of the public trust. A womam whose friend died in the massacre told me that she had put off seeing the film, but would soon. A psychologist I know was moved and impressed by the tact of Villeneuve’s work. And after five weeks on Quebec screens, the picture had earned an impressive $1,429,848.

On the other hand, the English version of Polytechnique, a double shoot in two languages, tanked miserably, and the audience numbers for the French version dropped abruptly in late February, yet it remained in the top ten. Some commentators speculated that Anglo Quebeckers don’t care about 12/6/89, but in reality, while they rarely flock to local movies, they might have opted for French in this case. As for the dwindling audience, it’s possible that certain prospective viewers stayed away when they realized that Polytechnique does not deliver a gorefest. On top of that, in the Oscar aftermath, moviegoers flocked to Slumdog Millionaire.

Polytechnique opens this month in Toronto, Vancouver, and Calgary.

Body Count

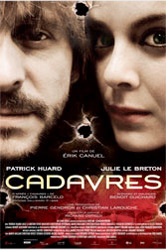

The methodically restrained Polytechnique is not on the same movie planet as another highly anticipated new release: Érik Canuel’s Cadavres. Canuel, whose Bon Cop Bad Cop made him one of Quebec’s most bankable directors, goes for berserk in this blood-drenched, poop-stained, ultra- stylized dark comedy about a brother and sister holed up in a ramshackle country house rapidly filling with corpses.

stylized dark comedy about a brother and sister holed up in a ramshackle country house rapidly filling with corpses.

In the opening scene of Cadavres, which premiered as the opening film of the 2009 Rendez-Vous du Cinéma Québécois (February 18-28), a taciturn oaf called Raymond (Patrick Huard) shoots his mother Solange (Sylvie Boucher) while speeding along a lost highway. Frenetic editing, what seems like baseball-sized grain, and rusty-yellow tinting enhance the moment of matricide, which Raymond claims is the only way he can express his love for Solange.

Before you can say “Fargo,” “David Lynch,” “Extreme Asian Cinema,” or other obvious influences, Raymond calls sister Angèle (Julie Le Breton) as the camera circles endlessly around his phone booth, located near an atmospherically lonely gas station. Canuel, fond of sporting punky bling, is one of the few Quebec filmmakers who professes a love of genre style. He also has an eye for Julie Le Breton’s voluptuously statuesque body, the whole point of a long sequence in which Angèle showers and dries herself in her brother’s presence.

sequence in which Angèle showers and dries herself in her brother’s presence.

On the verge of incest throughout Cadavres, Raymond and Angèle, who happens to be the star of a crummy TV action series out of Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill, face some challenges like what happened to their mother’s body? And how about that delicatessen of weird visitors from a heard of pigs to biker punks Paulo (Christopher Heyerdahl) and Paulette (Marie Brassard), natural-born lovers who get off on frolicking in a septic pond? Of greatest concern is the way each visit leads to yet another dead body in the basement. The comic book-style end credits of Cadavres give the impression that the picture might have been adapted from some underground bande dessinée, but in fact, Canuel and screenwriter Benoît Guichard based it on François Barcelo`s novel.

According to box-office tracking agency Cineac, Cadavres opened in 7th place, earning $113,258 on 56 screens. Not the best possible weekend, but like Polytechnique, it was up against the Slumdog. By the beginning of its third week, Cadavres had picked up a disappointing $279,339.

RVCQ 2009

An atypical opening night choice for the Rendez-Vous du Cinéma Québécois, a festival dedicated to screening much of the year’s local production, Cadavres didn’t get the kind of howling, foot-stomping reception it would have received at the FantAsia Genre Festival, which Canuel wholeheartedly supports. The closing film, Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette et Émile Proulx-Cloutier’s Les petits géants, a doc about  little kids who put on a performance of Verdi’s Le Bal Masqué, was more in character.

little kids who put on a performance of Verdi’s Le Bal Masqué, was more in character.

The 27th RVCQ played a selection of over 350 movies that included shorts, Québécois classics, and a sidebar of Mexican pictures in a crossover arrangement with the Festival Internacional de Cine en Guadalajara. The films were grouped into sections like Vues d’auteurs, Nouvelle vague, 100 % indépendant, Nos plus beaux films de … sport, A Taste of the Rendez-Vous, the fest’s outreach to the anglo community, and Box-Office, which screens the year’s biggest hits. Deemed a success by organizers, the 2009 edition drew 35,000 people.

Among the docs in view, Denys Desjardins’ De l’Office au Box-Office lamented the fall from the innocent days at the NFB (“l’Office”), when nobody thought about profitability, to the current obsession with scoring hits. The Rendez-vous also showed Brett Gaylor’s hot NFB/EyeSteelFilm copro, RIP: Remix Manifesto, which argues for a citizen’s right to cut and paste everything she finds on the Internet. In another mode, Martin Perreault’s Bianca Beacuhamp All Access 2: Rubberized celebrated a major cultural occasion: last year’s edition of Montreal’s hugely popular Fetish Weekend.

Despite its homey name, the Rendez-Vous is an expansive event that offers daily thematic sessions with filmmakers, free shindigs like the SeXXX and Cinema Cabaret, and art exhibitions. This year, cinematographer/photographer Thomas Vamos’ Lèche-vitrines (Window Shopping) presented dreamy images of multiple reflections in shop and restaurant windows. In the RVCQ’s program, “Leçons de cinéma,” the last of four classes was a production lesson with U.S. moviemaker Christine Vachon, whose impeccable taste resulted in pictures ranging from Boys Don’t Cry to I’m Not There. When the thoroughly engaging producer was asked by someone who might have had Polytechnique on her mind whether certain subjects should be banned from the screen, Vachon called that a “dangerous idea.”

Genie Vs. Jutra

When the Academy of Canadian Cinema and Television announced its 2009 Genie nominees, few were surprised that Benoît Pilon’s Ce qu’il faut pour vivre (The Necessities of Life), a serious contender for a Best Foreign-Language Film Oscar nomination, would place high on the list. But for some reason, Philippe Falardeau`s C’est pas moi, je le jure (It’s Not Me, I Swear!), one of the year’s strongest movies from any country, picked up only one nomination.

Falardeau`s C’est pas moi, je le jure (It’s Not Me, I Swear!), one of the year’s strongest movies from any country, picked up only one nomination.

A week later, It’s Not Me took two important prizes at the Berlin Film Festival, and went on to collect seven nominations in Quebec’s Prix Jutra competition. Then the Canadian Film and Television Producers’ Association gave Falardeau’s picture its Indie Award for best feature.

Apart from consideration of It’s Not Me, Genie and Jutra nominators disagreed about other prominent Quebec films. For instance, Yves-Christian Fournier’s Tout est parfait (see March 2008’s Inside Quebec) received seven Genie nominations, but only four Jutra nods that did not include best picture – an outcome that shocked passionate advocates of Fournier’s film about teen suicide.

Even more striking, Luc Picard’s elaborate fantasy film Babine (see December’s Inside Quebec) swept the Jutras with nine nominations while it was completely ignored by the Genies. Journalists noted that Picard was denied a best director nomination, but the apparent absurdity could be explained by the fact that nominators vote in their own professional category. While Picard is a highly respected actor, Babine is only his second shot at directing.

The Jutras and the Genies were also not in synch on Ce qu’il faut pour vivre (five Jutra nominations, eight from the Genies). Incidentally, the Quebec Film Critics’ Association, of which I’m a member, announced at the Rendez-Vous du Cinéma Québécois that it voted Ce qu’il faut best film of the year.

Happiness Is A Warm Hat

Unlikely to be nominated for any awards next year, Robert Ménard’s Le Bonheur de Pierre is a misfiring comedy about a Parisian university professor (French comic actor Pierre Richard), who discovers that his late aunt has left him an inn in Quebec’s spectacularly beautiful Saguenay region.

Pierre is both a philosophy teacher who believes he has discovered the secret to happiness, and a relentlessly beaming child-man who delights in the wild north during what looks like the most overcast winter ever. In his fur hat, Pierre snowshoes  over snowy hills and dales indulging in Davy Crockett fantasies.

over snowy hills and dales indulging in Davy Crockett fantasies.

Unfortunately, Pierre’s ambitious, fascinatingly flat-chested daughter (Sylvie Testud) would rather be hustling clients in Paris than traipsing around the backwoods. Even worse, the village mayor (Rémy Girard), who owns the only convenience store and runs the post-office, covets the inn and wants Pierre and Catherine out of it. In the hit comedy, La grande séduction, (Seducing Dr. Lewis), rural villagers do everything they can to lure a young doctor into staying with them forever. In this picture, the mayor and his pals try to get Pierre out of town by cutting off his electricity, screwing up his plumbing, and so on.

Ménard, who co-wrote and directed last year’s biggest hit, Cruising Bar 2, has a tendency to over-play and extend gags to the point that they become exhausted. He also keeps cutting back to the same shot, for instance Girard staring through binoculars like a general at war, as if a movie only needs a few key images. Despite hostile reviews, the comedy enjoyed a strong opening weekend, and by its 10th day of release, earned $279,339. Distressed by La Presse’s pan, writer-producer Guy Bonnier wrote a lengthy open letter to the daily, arguing that its movie guy failed to grasp the film’s wit and wisdom.

Screening with Le Bonheur de Pierre, the short ONF 70 ans celebrates the National Film Board in its 70th year. Directed by Jean-François Pouliot, who made La grande séduction, ONF 70 ANS frames a dynamic montage of NFB images, both unsettling and lyrical, with an on-camera yob complaining that the Board is a day-care centre for commies. The film is homage with a sense of humour.

![]() Maurie Alioff is a film journalist, critic, screenwriter and media columnist. He has written for radio and television and teaches screenwriting at Montreal`s Vanier College. A former editor for Cinema Canada and Take One, as well as other magazines, his articles have appeared in various publications including The Montreal Mirror and The New York Times.

Maurie Alioff is a film journalist, critic, screenwriter and media columnist. He has written for radio and television and teaches screenwriting at Montreal`s Vanier College. A former editor for Cinema Canada and Take One, as well as other magazines, his articles have appeared in various publications including The Montreal Mirror and The New York Times.