Once Were Brothers on Crave

by Maurie Alioff

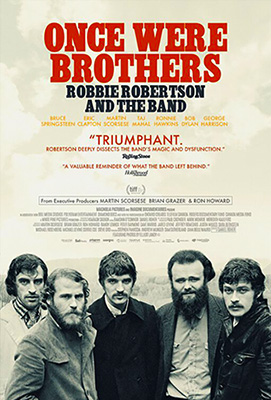

(April 16 2020 – Montréal, Québec) Daniel Roher’s documentary Once Were Brothers launched with Toronto producer Peter Raymont of White Pine Pictures and Bell Media’s Crave, which is now streaming the film on its online platform. Crave’s debut, earlier than originally programmed, followed North American theatrical screenings. The switch was clearly motivated by the Corona Pandemic.

Randy Lennox, Bell Media President told Market Insider: “We’re thrilled to finally debut this incredible documentary film on the streaming service where it began. With so many Canadians currently at home, it’s the perfect time to take a break and go on a journey revisiting the story of one of Canada’s larger-than-life cultural icons.”

The doc, based on Robertson’s memoir Testimony, was a natural for Crave, which Robertson praised at the Toronto International Film Festival’s gala opening night screening. (The service is also playing The Last Waltz, allowing viewers enjoy a The Band during Corona double bill.

Via Robertson, Martin Scorsese, whose The Last Waltz lushly documented The Band’s final concert, came on board, as did Imagine Entertainment’s director-producer team, Ron Howard and Brian Grazer (A Beautiful Mind, Apollo 13). At TIFF’s press conference for the picture, the duo fielded questions with Robertson and Roher, and in the room, Justin Wilkes and Sara Bernstein of Imagine’s new documentary division, looked on. At one point, Ron Howard beamed that the mega-distributor Magnolia has acquired the doc at TIFF and will handle it worldwide.

Of all legendary rock and roll bands, the most legendary, you could even say self-consciously legendary, was The Band. Levon Helm, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, Garth Hudson, and of course Robbie Robertson emerged from Toronto rocker Ronnie Hawkins’s The Hawks, became Bob Dylan’s backup musicians, and then jammed and wrote songs with Bob in Woodstock, New York. In the midst of that bubbling creativity The Band, (as if they were the ultimate band, what movie producer Brian Grazer calls the “quintessential” band), released their first album, Music from Big Pink. It’s fifty years old this year.

There was nothing else like Big Pink. Songs like “The Weight” and “The Night They Tore Old Dixie Down,” highlighted in Once Were Brothers, seemed to have always been there, deeply ingrained Americana. The group’s solemn, bearded organist, Garth Hudson, looked like he somehow popped out of a 19th century portrait of a revivalist. The others resembled outlaws, preachers, and itinerant minstrel men with haunted, otherworldly voices to match. They looked like they rode with John Wesley Harding, the gunslinger Dylan once celebrated.

At the press conference, Robertson talked with his usual confident eloquence about a variety of subjects. On stage with the 76-year-old songwriter and musician, twenty something director Daniel Roher was incredulous that his film got programmed as the first Canadian documentary to open TIFF. “I can’t imagine a greater compliment then opening at the Toronto film Festival with a young Torontonian director,” said Robertson, “and this kind of team. It doesn’t get better.”

Robbie Robertson, whose upcoming album is called Cinematic, and wrote the score for Scorsese’s The Irishman, is a movie lover who once dreamt of collaborating with Ingmar Bergman. Yes, the Americana rock ‘n’ roller “was like first in line when a new Bergman film came out. A lot of inspiration for songs that I wrote came from movie scripts,” he continued, recalling a bookstore on 47th Street in New York City, (probably the Gotham Book Mart). In that special place, he could “buy the script for Persona, for The Seventh Seal, for 8 ½, for Bunuel films, for Kurosawa, for Howard Hawks, for John Ford.

“It was so wonderful to go behind that mystery of ‘I’m seeing a movie, and saying Wow, how did they do that?’ I needed to go deeper, I needed to know more. And I got really addicted to reading those scripts.”

While most Band fans assumed they were really the country boys they seemed to be, Robertson says, “I thought of this group as characters that I was casting in roles in the songs that I was writing. I would say, ‘You should sing this because of the story that I’m trying to tell. You should be the lead in this one, and you are going to sing the harmony, and you’re going to come in on the chorus.’ I don’t know of any other group, and I don’t know any other songwriter that comes from this kind of background. The songs were like little movies.”

Executive producer Brian Grazer, who unlike his long-time collaborator Ron Howard, has been immersed in music since childhood, explained what attracted him to Once Were Brothers. “It was the beginning of a movement, and we can actually proof this out almost like a cinematic equation, which is exactly what you do by the way in documentaries. You have a thesis, and you try to proof it out cinematically. I thought that Robbie and The Band is the quintessential survival story. It’s called The Band for a reason.”

The film recounts how members of the group survived wild times, not to mention infuriated folk music acolytes pelting the stage because Bob Dylan had “gone electric” during the sixties tour documented by D.A. Pennebaker in his ground-breaking cinéma vérité film, Don’t Look Back.

It was a charge that seems even more ridiculous now than it did then. “Talk about survival,” Robertson laughed. He was said to have modified his guitar strap so he could use his instrument as a weapon during the Dylan tour.

Once Were Brothers points out how wild times spun out of control into heroin popping and other addictions. Richard Manuel hung himself; Rick Danko and Levon Helm got sick and died prematurely.

Looking back on chaos, Robertson said at the press conference, “Some years ago, we didn’t really understand alcoholism and addiction. Today, when I look back on it, I feel very sad that we didn’t have the tools to help one another in this group. We probably did everything you’re not supposed to do. There wasn’t a support system, and so I carry a bit of sadness about that because I lost three of my brothers in this group.”

“Although I’m motoring along,” Robertson continued, “and I’ve got so many things I want to discover and get to in my work, whenever I go to that place in my heart where I think ‘I lost these guys,’ and I was helpless, it’s a devastating feeling.”

Brian Grazer’s credits include many projects that feature music: the Eminem film, 8 Mile, the Beatles doc 8 Days a Week, the just released Pavarotti (both directed by Ron Howard), and TV series like Empire.

Given the high-scoring track record of Imagine Entertainment, it’s surprising that Ron Howard and Brian Grazer are not always on the same page. “We often come at things very differently,” Howard explained, “and then reach an accord. “We do access on very important parts like theme,” Grazer said, “but we experience life almost entirely differently.”

Both moviemakers agree that any movie is, as Howard puts, “editorial. I don’t care whether it is journalism, or a scripted peace, or a documentary. Of course, it’s a point of view, an expression. Who knows what the truth is? It’s your sense of it.”

In the case of Once Were Brothers, Daniel Roher felt “like an archaeologist” seeking out, reviewing, and selecting huge amounts of archival material. “My creative instinct put it on a rocket ship and went to the moon.” During the most extensive research he ever did, Roher found accounts of the controversial feud that rocked The Band. Various observers have differing opinions about it.

Robertson offered his truth about the distance that grew between him and drummer-singer Levon Helm, the group’s sole American-born musician. “I love Levon,” said Robertson. “To me, we were brothers, and we went through the war together. We did so many amazing things in our life together. Years later, and I wasn’t there, for him it went to another place, and I had no control over that. So I just stepped aside. People are going to go where they’re going to go. I just take care of what’s on my side of the street.”

Since the doc is rooted in Canada, a country that supports film production, Howard mused about the fact that some countries like Germany and Italy are not supporting cultural identity. In fact, talented Swedish moviemakers are shooting in other countries (Midsommar in Hungary for example), because Sweden offers zero tax credits, or other benefits.

Grazer thinks maybe Canadians take government support of culture for granted. “You’re good people,” he said. “Humility as an element to a team is really important in Canada. Making a movie is teams of hundreds of people, you have to evangelize your reason for existence with a worthy subject.” It’s essential “to have a team that’s humble, and has the same level of work ethic, the desire to win.”

Near the end of the press conference, the focus returned to the music at the core of the film. Responding to a question about changes in music since The Band’s heyday, Robertson said, ”We were in a generation when music was the voice of that generation. And so you felt a responsibility to talk about something, tell a story about something that had deeper meaning to it. But nowadays, they don’t have that kind of pressure. Our leaders were being assassinated. There was this terrible war going on. The unification of that generation had a lot to do with the soundtrack.”The culture now is about “have a good time. And it’s also called, ‘Tell us about your last relationship and the break up.’ (Robertson seems to have forgotten Bob Dylan’s numerous break up songs, especially the entire Blood on the Tracks album.) That’s what so many records are made about today. Me, I don’t care about your last relationship. But go ahead and vent. It’s okay.”

Also see: The cast and crew of Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and the Band.

![]() Maurie Alioff is a film journalist, critic, screenwriter and media columnist. He has written for radio and television and taught screenwriting at Montreal’s Vanier College. A former editor for Cinema Canada and Take One, as well as other magazines, he is affiliated with the Quebec media industry publication, CTVM.Info and is a regular contributor to Northernstars.ca: The Canadian Movie Database. His articles have appeared in various publications, including Canadian Cinematographer, POV Magazine, and The New York Times.

Maurie Alioff is a film journalist, critic, screenwriter and media columnist. He has written for radio and television and taught screenwriting at Montreal’s Vanier College. A former editor for Cinema Canada and Take One, as well as other magazines, he is affiliated with the Quebec media industry publication, CTVM.Info and is a regular contributor to Northernstars.ca: The Canadian Movie Database. His articles have appeared in various publications, including Canadian Cinematographer, POV Magazine, and The New York Times.