|

|

|

| Inside Québec – June 2008by Maurie Alioff |

|

|

|

|

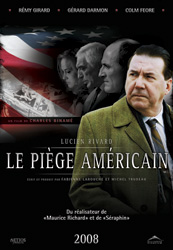

Canadian GangsterAfter stickhandling mainly Québécois-centric productions like Maurice Richard (2007) and Séraphin: un homme et son péché (2002), Charles Binamé’s ambitious new movie is literally all over the map. Le piège américain (The American Trap) shuttles viewers from Havana and Montreal to Louisiana and Texas as it follows the criminal machinations of its protagonist, Lucien Rivard. A half-forgotten legend, the real-life gangster played dangerous games with the Mafia in pre-revolutionary Cuba, imported heroin into the U.S., assisted C.I.A. undercover work, and according to the film, was linked to major players involved in JFK’s assassination.Ghostly scenes in the movie depict Lee Harvey Oswald, Robert Kennedy and notorious FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, not to mention a spectacularly degenerate Jack Ruby, who once bailed Rivard out of a Cuban slammer. According to the film’s co-screenwriter, Fabienne Larouche, Le piège américain was inspired by Pete Bondurant, a Rivard-like character who makes startling appearances in James Ellroy’s provocative novel, American Tabloid. While Bondurant is a mythic French-Canadian giant fond of cracking people’s skulls open with his fists, Rémy Girard plays Rivard naturalistically, offering an impressively sustained portrait of a mid-level operator. The film’s mobster is an implacable tough guy with a bullet-proof scowl.In Le piège américain, Binamé deploys a wide range of stylistic flourishes including washed-out colour, deliberately heavy grain, faux archival footage, and antique transitions between shots. Period cars, guns, and shades are impeccably detailed. Le piège américain is not merely set during the fifties and sixties, the filmmakers strive to make it look as if it was shot during the period when the story unfolds. The picture is loaded with the atmosphere of lonely American backroads and cruddy bars, but in the end, it flexes too much muscle, straining to be brilliant.Seeing Le piège américain before its release, I wondered how the movie would play to audiences anticipating a gangster picture like Brian De Palma’s Scarface. While De Palma and Oliver Stone’s garish masterpiece pushes operatic violence and emotional confrontations to the point that their saga about a Cuban-American gangster becomes comical, Binamé’s film is all about moody dialogue scenes and intricate conspiracies. Certainly, The American Trap does not allow for romance between its beast and archetypal blond beauty, in this case an angelic junkie-whore called Rose (Janet Lane). It’s a grimly uncompromising picture that rarely deviates from its vision of corruption, embodied more by a ruthless C.I.A. agent (Colm Feore) than by Rivard himself.I’m sure that Le piège américain will be a Genie and Jutra winner when award season rolls out, but since its release in mid-May, the movie has been a box-office disappointment. As I write, 44 screens have yielded $325,457, numbers which must be hard-to-swallow for the unbelievably prolific TV writer Fabienne Larouche (1440 episodes for one of her many series!), making her screenwriting debut. Perhaps Quebec audiences don’t want their mainstream pictures to venture too far from home, portraying English and Spanish-speaking characters. Maybe films from other places, whether auteur gems or blockbusters like the hugely popular Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, fulfil the need for celluloid travelling.Denis Does CannesCannes 2008 (May 15-25) screened two Canadian films in its official competition: Atom Egoyan’s Adoration and Fernando Meirelles’ Blindness, which was written by Toronto’s Don McKellar, and is a three-way coproduction with Brazil and Japan. Neither won a competition jury award, but this year’s Ecumenical jury prize went to Egoyan’s new movie.In Quebec, the media barely registered McKellar and Egoyan’s passage through the festival, reserving its excitement for Denis Villeneuve’s Grand Prix Canal+ for best short. According to long-time Cannes observer, Jean-Pierre Tadros, Cannes’ artistic director, Thierry Fremaux, was annoyed that the Official Selection passed on Villeneuve’s Next Floor, which the criminal machinations of its protagonist, Lucien Rivard. A half-forgotten legend, the real-life gangster played dangerous games with the Mafia in pre-revolutionary Cuba, imported heroin into the U.S., assisted C.I.A. undercover work, and according to the film, was linked to major players involved in JFK’s assassination.Ghostly scenes in the movie depict Lee Harvey Oswald, Robert Kennedy and notorious FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, not to mention a spectacularly degenerate Jack Ruby, who once bailed Rivard out of a Cuban slammer. According to the film’s co-screenwriter, Fabienne Larouche, Le piège américain was inspired by Pete Bondurant, a Rivard-like character who makes startling appearances in James Ellroy’s provocative novel, American Tabloid. While Bondurant is a mythic French-Canadian giant fond of cracking people’s skulls open with his fists, Rémy Girard plays Rivard naturalistically, offering an impressively sustained portrait of a mid-level operator. The film’s mobster is an implacable tough guy with a bullet-proof scowl.In Le piège américain, Binamé deploys a wide range of stylistic flourishes including washed-out colour, deliberately heavy grain, faux archival footage, and antique transitions between shots. Period cars, guns, and shades are impeccably detailed. Le piège américain is not merely set during the fifties and sixties, the filmmakers strive to make it look as if it was shot during the period when the story unfolds. The picture is loaded with the atmosphere of lonely American backroads and cruddy bars, but in the end, it flexes too much muscle, straining to be brilliant.Seeing Le piège américain before its release, I wondered how the movie would play to audiences anticipating a gangster picture like Brian De Palma’s Scarface. While De Palma and Oliver Stone’s garish masterpiece pushes operatic violence and emotional confrontations to the point that their saga about a Cuban-American gangster becomes comical, Binamé’s film is all about moody dialogue scenes and intricate conspiracies. Certainly, The American Trap does not allow for romance between its beast and archetypal blond beauty, in this case an angelic junkie-whore called Rose (Janet Lane). It’s a grimly uncompromising picture that rarely deviates from its vision of corruption, embodied more by a ruthless C.I.A. agent (Colm Feore) than by Rivard himself.I’m sure that Le piège américain will be a Genie and Jutra winner when award season rolls out, but since its release in mid-May, the movie has been a box-office disappointment. As I write, 44 screens have yielded $325,457, numbers which must be hard-to-swallow for the unbelievably prolific TV writer Fabienne Larouche (1440 episodes for one of her many series!), making her screenwriting debut. Perhaps Quebec audiences don’t want their mainstream pictures to venture too far from home, portraying English and Spanish-speaking characters. Maybe films from other places, whether auteur gems or blockbusters like the hugely popular Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, fulfil the need for celluloid travelling.Denis Does CannesCannes 2008 (May 15-25) screened two Canadian films in its official competition: Atom Egoyan’s Adoration and Fernando Meirelles’ Blindness, which was written by Toronto’s Don McKellar, and is a three-way coproduction with Brazil and Japan. Neither won a competition jury award, but this year’s Ecumenical jury prize went to Egoyan’s new movie.In Quebec, the media barely registered McKellar and Egoyan’s passage through the festival, reserving its excitement for Denis Villeneuve’s Grand Prix Canal+ for best short. According to long-time Cannes observer, Jean-Pierre Tadros, Cannes’ artistic director, Thierry Fremaux, was annoyed that the Official Selection passed on Villeneuve’s Next Floor, which  got slotted into the Cannes sidebar, the Semaine de la Critique.Next Floor is a macabre 11-minute film depicting a grotesque, never-ending banquet in a mysterious building where overloaded tables fall through collapsing floors. Recalling Marco Ferreri’s 1973 satire La grande bouffe, the little film about gluttony was dreamed up by the movie’s producer, Phoebe Greenberg, whose avant-garde theatre work favours the absurd and grotesque. To achieve her movie debut, Greenberg commissioned Jacques Davidts to write the script and Villeneuve to direct. Greenberg is a long-time fan of the 41-year-old’s work, particularly Maelström (2000), and its narrator, a baleful, gravely voiced talking fish.Next Floor marks Villeneuve’s return to the international film scene. For years after the Next Big Thing status that Maelström bestowed on him, Villeneuve kept a low profile, honing his writing skills and inducing Whatever Happened To Him? speculation.Now Villeneuve has two new features on the horizon. Polytechnique, in postproduction, sounds like a departure for the moviemaker, whose Un 32 août sur terre (1998) and Maelström (2000), which kick-started actress Marie-Josée Croze’s international career, were idiosyncratic dark comedies. Polytechnique, its budget enhanced by $3.1 million from Telefilm Canada, is a docudrama recounting the terrifying 1989 massacre of 14 female students in Montreal`s École Polytechnique. As he completes the movie, Villeneuve is preparing to shoot Incendies, an adaptation of Wajdi Mouawad’s play about twins unravelling dark family secrets on a trip through Lebanon.Shattered ChristalIncendies is on a slate of upcoming pictures backed by the distribution arm of Christal Films, until recently regarded as one of Quebec’s hottest companies. The operation’s sudden nosedive could spell trouble for Villeneuve’s gestating picture.Just before Cannes, where founder and president Christian Larouche should have been dealmakng, Christal Films Distribution sought and received bankruptcy protection. Meanwhile chez Seville Films, possibly Larouche’s number one competitor, the future looks bright. Acquired last fall by the deep-pocketed Entertainment One, which set up a co venture with Robert Lantos’ new company, Maximum Films, Seville picked up distribution rights for several Cannes’ award winners and hot items. These include Israeli Ari Folman’s reportedly stunning animation feature, Waltz with Bashir.A few weeks before Christal’s bankruptcy announcement, Montreal producer Kevin Tierney (Bon Cop Bad Cop) wasn’t overly concerned about the ongoing shakeup in Canada’s vitally important distribution scene. “On the Richter Scale, I think there was a 3.2 or something,” Tierney said. However, he also told me that the fall of Christal would be very scary, “a major blow.”After all, if the company that produced and released Les Trois p’tits cochons and other hits folds, how will less successful film houses see their future? And what impact will that pessimism have on not just Quebec’s, but Canada’s film and TV industry.Love, Savagery, and The Big Chill ReduxSpeaking of Kevin Tierney, the producer just wrapped an inter-provincial coproduction between his Park-Ex Pictures and Newfoundland moviemaker Barbara Doran’s Morag Loves Company. Directed by John N. Smith, written by Des Walsh, (Smith’s collaborator on The Boys of St. Vincent and Random Passage), got slotted into the Cannes sidebar, the Semaine de la Critique.Next Floor is a macabre 11-minute film depicting a grotesque, never-ending banquet in a mysterious building where overloaded tables fall through collapsing floors. Recalling Marco Ferreri’s 1973 satire La grande bouffe, the little film about gluttony was dreamed up by the movie’s producer, Phoebe Greenberg, whose avant-garde theatre work favours the absurd and grotesque. To achieve her movie debut, Greenberg commissioned Jacques Davidts to write the script and Villeneuve to direct. Greenberg is a long-time fan of the 41-year-old’s work, particularly Maelström (2000), and its narrator, a baleful, gravely voiced talking fish.Next Floor marks Villeneuve’s return to the international film scene. For years after the Next Big Thing status that Maelström bestowed on him, Villeneuve kept a low profile, honing his writing skills and inducing Whatever Happened To Him? speculation.Now Villeneuve has two new features on the horizon. Polytechnique, in postproduction, sounds like a departure for the moviemaker, whose Un 32 août sur terre (1998) and Maelström (2000), which kick-started actress Marie-Josée Croze’s international career, were idiosyncratic dark comedies. Polytechnique, its budget enhanced by $3.1 million from Telefilm Canada, is a docudrama recounting the terrifying 1989 massacre of 14 female students in Montreal`s École Polytechnique. As he completes the movie, Villeneuve is preparing to shoot Incendies, an adaptation of Wajdi Mouawad’s play about twins unravelling dark family secrets on a trip through Lebanon.Shattered ChristalIncendies is on a slate of upcoming pictures backed by the distribution arm of Christal Films, until recently regarded as one of Quebec’s hottest companies. The operation’s sudden nosedive could spell trouble for Villeneuve’s gestating picture.Just before Cannes, where founder and president Christian Larouche should have been dealmakng, Christal Films Distribution sought and received bankruptcy protection. Meanwhile chez Seville Films, possibly Larouche’s number one competitor, the future looks bright. Acquired last fall by the deep-pocketed Entertainment One, which set up a co venture with Robert Lantos’ new company, Maximum Films, Seville picked up distribution rights for several Cannes’ award winners and hot items. These include Israeli Ari Folman’s reportedly stunning animation feature, Waltz with Bashir.A few weeks before Christal’s bankruptcy announcement, Montreal producer Kevin Tierney (Bon Cop Bad Cop) wasn’t overly concerned about the ongoing shakeup in Canada’s vitally important distribution scene. “On the Richter Scale, I think there was a 3.2 or something,” Tierney said. However, he also told me that the fall of Christal would be very scary, “a major blow.”After all, if the company that produced and released Les Trois p’tits cochons and other hits folds, how will less successful film houses see their future? And what impact will that pessimism have on not just Quebec’s, but Canada’s film and TV industry.Love, Savagery, and The Big Chill ReduxSpeaking of Kevin Tierney, the producer just wrapped an inter-provincial coproduction between his Park-Ex Pictures and Newfoundland moviemaker Barbara Doran’s Morag Loves Company. Directed by John N. Smith, written by Des Walsh, (Smith’s collaborator on The Boys of St. Vincent and Random Passage), Love and Savagery portrays a star-crossed romance between a Canadian poet and an Irish woman who has given herself to the church.Originally an international copro with Ireland’s Subotica Entertainment, the $6.5-million feature is now strictly Canadian. “Things got to be too complicated,” says Tierney, who points out that the high cost of making movies with filmmakers in other nations often outweighs the benefits.As the Love and Savagery shoot wound down in Newfoundland, Tierney and his collaborators were rattled by some wacky news. Canadian border officials had seized footage shot in Ireland and transported to Montreal for processing. With a title like Love and Savagery, the agents reasoned, this has got to be some kind of weirdo porno. Tierney is relieved that the officials backed off from their plan to subject the delicate 35mm film to potentially damaging RCMP lab work. But he worries that the episode might have been inspired by all the talk about Bill C-10, ominous legislation that could have a devastating impact on Canadian movies.Recalling the height of political correctness, or the era dominated by NFB founder John Grierson’s austere views, C-10 could stifle the filmmaking imagination. The Harper government legislation disciplines naughty producers by forcing them to return vitally important tax credits granted to projects deemed sinful by a board of Conservative appointees. Appearing before the Senate Committee that has been hearing the concerns of film people like Sarah Polley and Paul Gross, director Jean Pierre Lefebvre said, “If a democratic government like ours has no faith in its own institutions, in its own Criminal Code, and in its own Charter of Rights and liberties, it would not be worthy of the confidence of Canadian citizens.”More recently veteran producer Roger Frappier said that his candidly sexual film Borderline would never have been financed and made with C-10 in place.“If this law is adopted,” Frappier told the committee, “it would have catastrophic consequences for our cinema. Liberty of expression and liberty of creation are priceless. The project of Bill C-10 endangers the Quebec and Canadian film industries.”First PeopleA June event, the Festival Présence autochtone celebrates native artistic expression from film and videomaking to engraving, sculpture, and music. The fest runs in various Montreal locations as well as the nearby Mohawk reserve of Kahnawake. At this year’s edition of the First People’s Festival, movies and videos from Canada, the U.S., Mexico, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, France, the U.K., Australia, Love and Savagery portrays a star-crossed romance between a Canadian poet and an Irish woman who has given herself to the church.Originally an international copro with Ireland’s Subotica Entertainment, the $6.5-million feature is now strictly Canadian. “Things got to be too complicated,” says Tierney, who points out that the high cost of making movies with filmmakers in other nations often outweighs the benefits.As the Love and Savagery shoot wound down in Newfoundland, Tierney and his collaborators were rattled by some wacky news. Canadian border officials had seized footage shot in Ireland and transported to Montreal for processing. With a title like Love and Savagery, the agents reasoned, this has got to be some kind of weirdo porno. Tierney is relieved that the officials backed off from their plan to subject the delicate 35mm film to potentially damaging RCMP lab work. But he worries that the episode might have been inspired by all the talk about Bill C-10, ominous legislation that could have a devastating impact on Canadian movies.Recalling the height of political correctness, or the era dominated by NFB founder John Grierson’s austere views, C-10 could stifle the filmmaking imagination. The Harper government legislation disciplines naughty producers by forcing them to return vitally important tax credits granted to projects deemed sinful by a board of Conservative appointees. Appearing before the Senate Committee that has been hearing the concerns of film people like Sarah Polley and Paul Gross, director Jean Pierre Lefebvre said, “If a democratic government like ours has no faith in its own institutions, in its own Criminal Code, and in its own Charter of Rights and liberties, it would not be worthy of the confidence of Canadian citizens.”More recently veteran producer Roger Frappier said that his candidly sexual film Borderline would never have been financed and made with C-10 in place.“If this law is adopted,” Frappier told the committee, “it would have catastrophic consequences for our cinema. Liberty of expression and liberty of creation are priceless. The project of Bill C-10 endangers the Quebec and Canadian film industries.”First PeopleA June event, the Festival Présence autochtone celebrates native artistic expression from film and videomaking to engraving, sculpture, and music. The fest runs in various Montreal locations as well as the nearby Mohawk reserve of Kahnawake. At this year’s edition of the First People’s Festival, movies and videos from Canada, the U.S., Mexico, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, France, the U.K., Australia,  and New Zealand screen in competition. One of the festival’s highlights, Mohawk filmmaker Tracey Deer’s Club Native, investigates the dilemmas faced by Aboriginals who dare to marry whites and have children with them.Like Deer’s 2005 film Mohawk Girls, Club Native was made by the National Film Board, the longtime producer of docs by Canada’s most renowned native filmmaker, Alanis Obomsawin. The Board chose the fest to launch 270 Years of Resistance, a boxed set of four Obomsawin films. The event’s honorary president, Obomsawin told me recently that she’s never stopped being “excited and moved” by the native stories she’s been telling since the 1960’s.“I love this festival,” Obomsawin continued. “And they’ve really had to struggle for so many years to get to where they are now.” Why was it so hard? “It’s like everything else. If changes have come to us, it’s because we fought for them over many generations.”Gilles for SaleIn an article for Take One Magazine, I once described director Gilles Carle’s movies as “vivid, effervescent and sometimes unapologetically lurid.” A maverick to the core, Carle’s unbridled energy animated the spaghetti-western style action film Red (1970), the erotic reverie, L’Ange et la femme (1977), the literary and New Zealand screen in competition. One of the festival’s highlights, Mohawk filmmaker Tracey Deer’s Club Native, investigates the dilemmas faced by Aboriginals who dare to marry whites and have children with them.Like Deer’s 2005 film Mohawk Girls, Club Native was made by the National Film Board, the longtime producer of docs by Canada’s most renowned native filmmaker, Alanis Obomsawin. The Board chose the fest to launch 270 Years of Resistance, a boxed set of four Obomsawin films. The event’s honorary president, Obomsawin told me recently that she’s never stopped being “excited and moved” by the native stories she’s been telling since the 1960’s.“I love this festival,” Obomsawin continued. “And they’ve really had to struggle for so many years to get to where they are now.” Why was it so hard? “It’s like everything else. If changes have come to us, it’s because we fought for them over many generations.”Gilles for SaleIn an article for Take One Magazine, I once described director Gilles Carle’s movies as “vivid, effervescent and sometimes unapologetically lurid.” A maverick to the core, Carle’s unbridled energy animated the spaghetti-western style action film Red (1970), the erotic reverie, L’Ange et la femme (1977), the literary adaptation, Maria Chapdelaine (1983), pop surrealism in Pudding Chomeur (1996), and his greatest picture, the haunting satirical fable, La Vraie Nature de Bernadette (1972).Stricken by Parkinson’s disease, Carle has reached a point where he needs round-the-clock care. To help fund it, Montreal arthouse, the Cinéma Beaubien organized an “expo-vente” of engravings Carle made in 1998, riding a rush of energy from the levadopa that treats Parkinsonian symptoms. The theme of the pictures: “Variations sur un t’aime.” Carle’s art has always been as playful and colourful as his movies. adaptation, Maria Chapdelaine (1983), pop surrealism in Pudding Chomeur (1996), and his greatest picture, the haunting satirical fable, La Vraie Nature de Bernadette (1972).Stricken by Parkinson’s disease, Carle has reached a point where he needs round-the-clock care. To help fund it, Montreal arthouse, the Cinéma Beaubien organized an “expo-vente” of engravings Carle made in 1998, riding a rush of energy from the levadopa that treats Parkinsonian symptoms. The theme of the pictures: “Variations sur un t’aime.” Carle’s art has always been as playful and colourful as his movies. |

|

Maurie Alioff is a film journalist, critic, screenwriter and media columnist. He has written for radio and television and teaches screenwriting at Montreal’s Vanier College. A former editor for Cinema Canada and Take One, as well as other magazines, his articles have appeared in various publications including The Montreal Mirror and The New York Times. |

|

| Inside Québec – Archive: November 2007 December 2007 January 2008 February 2008 March 2008 April 2008 May 2008 |

|

|

![]()

![]()